U.S. & Aussie research labs — is earth 'greening' or 'greenhousing'?

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (Christian Examiner) – The earth has absorbed about 16 percent more atmospheric carbon dioxide from 1901 to 2010 than expected.

Scientists at the Climate Change Institute of the U.S. Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory published these findings online, Oct. 13, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The U.S. climate change study reinforces findings published in 2013 by climatologists at Australia's national science agency, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial research Organization, also explaining the phenomenon of global greening in terms of increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Both studies show the earth is greening in response to more CO2 in the air, lessening the greenhouse effect. Consequently each could contribute an explanation for the "pause" in global warming, described as a hiatus by one NASA scientist, that has lasted about 15 years.

Essentially, the CCI study looked at how trees and plants process carbon through mesophyll diffusion, which basically describes the rate of gas exchange (oxygen for carbon dioxide), or more specifically, the spread of CO2 in a plant through photosynthesis.

They concluded that plants actually absorbed 1,057 billion tons of carbon as opposed to the predicted 915 billion tons, an approximate 16 percent increase, and emphasized the significance of this discovery in terms of the predictive inadequacy of current earth system models which do not account for the increased photosynthesis.

"Understanding and accurately predicting how global terrestrial primary production responds to rising CO2 concentrations is a prerequisite for reliably assessing the long-term climate impact of anthropogenic fossil CO2 emissions."

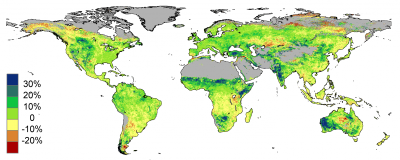

The Australian study, on the other hand, used satellite images of the earth taken from 1982 through 2010, to analyze changes in foliage on earth. Other studies have speculated on the cause for a greening effect that has been observed for decades. But this study, led by environmental physicist Randall Donohue, took measures to avoid variances related to differences in rainfall, temperature, sunlight and land use in order to see what effect increased carbon dioxide levels contributed.

Measuring changes in maximum foliage cover of warm, arid regions in Australia, North America, the Middle East and Africa, they found CO2 fertilization related to an 11 percent increase in foliage across the globe.

"Overall, our results confirm the direct biochemical impact of the rapid increase in [atmospheric carbon dioxide] over the last 30 years on terrestrial vegetation is an influential and observable land surface process," according to the report.

In a press release that accompanied the publishing of results in the peer-reviewed Geophysical Research Letters, Donohue said he was encouraged about the positive aspects of the findings but also offered caution about possible negative effects that need to be considered.

"On the face of it, elevated CO2 boosting the foliage in dry country is good news and could assist forestry and agriculture in such areas," he said. "[H]owever there will be secondary effects that are likely to influence water availability, the carbon cycle, fire regimes and biodiversity, for example."

Both studies join a growing body of evidence that the earth is more robust in responding to man-made influences on the environment than conceded by some segments of the scientific community.

Earlier this year scientists discovered a naturally occurring, salinity-driven, 30-year cycle in the Atlantic Ocean that mediated atmospheric temperatures, contributing to a centuries-old pattern of global warming slowdown and acceleration.

Another study in 2008 concluded satellite observations show much more energy is lost to space during and after warming than climate models show, suggesting cloud cover regulates earth temperature.

Together, these scientific discoveries appear to point to a design of stabilizing processes in nature that regulate variances in the earth's eco systems including those changes caused by manmade influences. Scientists arguing this position say at the least the departures represented in these and similar studies show climate models cannot explain the differences using traditional theories.